|

The Art and Nature of Fresco Main Page Introduction The Feminine & Fresco Creation Choosing a Wall Designing Murals Lime & Sand Plastering Color Painting Gallery Artist Biography Who Owns a Work of Art? Women Muralists Fresco Links Contact Us A Life in Art and Spirituality |

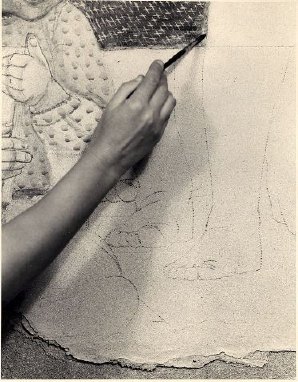

The Feminine and Fresco Creationby Sr. Lucia Wiley, CHSFresco painting is not romantic work, it is dirty, hard, physical labor, under the most trying of conditions. Noise on the site is very often deafening; extremes of heat and cold are common; bad light is all too often an unfortunate reality; wet work spaces and damp clothing must be tolerated; and the constant coming and going of people is disruptive. Needless to say creating a fresco is an arduous process. And as discussed in the other sections of the website, there are many, many critical components that require long term dedication to the mural before you actually begin to paint. So not only must the artist possess a vision and love for long term projects, she must have a strong intellect, a good measure of patience, masterful painting skills, and a good dose of physical strength.

Needless to say creating a fresco is an arduous process. And as discussed in the other sections of the website, there are many, many critical components that require long term dedication to the mural before you actually begin to paint. So not only must the artist possess a vision and love for long term projects, she must have a strong intellect, a good measure of patience, masterful painting skills, and a good dose of physical strength.Throughout history, fresco—as with the majority of the fine arts—has been a male dominated medium. It has been viewed as a masculine process particularly because of the extreme demands it places upon the artist. But I would like to make it known that the opposite is true: The process of creating a fresco is actually very feminine—feminine in the highest sense of the word. Woman by nature is a nurturer and fresco painting requires nurturing. The first reason I believe this is that the length of time it takes to prepare for the painting requires a highly dedicated and care-giving nature. Whether you prepare all of the material yourself or oversee their preparation, the time is long before you actually begin the final and wonderful stage of painting into the wet plaster. The determination to carry a project through months and years of preparation (which controls the quality and longevity of the fresco's existence) is a quality that has been highly developed in women through thousands of years of caring for children. The second reason comes from personal experience. During the painting hours the intonaco is like a living being, it has changing needs and capabilities. Of course those needs are not stated verbally but must be sensed and immediately responded to by the painter. It requires a sensitive, intuitive and nurturing ability to develop that living surface into a work of art. With care the life of the living plaster can be extended up to 17 hours. In my own work, I call this aspect of the process the "mothering principle," for whether we are mothers or not, intuition and nurturing are feminine gifts that echo the role of a mother. © the estate of Lucia Wiley; used by permission |